What is a post-incident review?

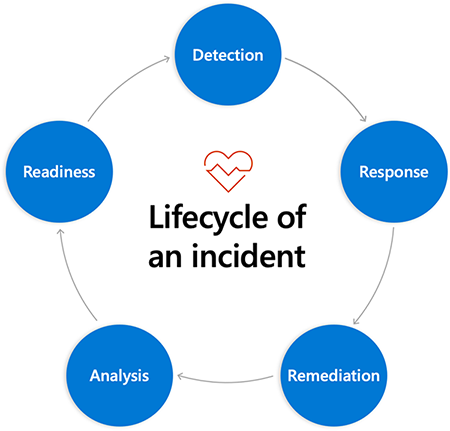

We've mentioned this in a previous module in this learning path, but as a quick review, incidents have a lifecycle that looks like this:

An incident moves through these phases:

- Detection: When we first notice that there's a problem (ideally from our monitoring system before a customer notices or complains);

- Response: We snap into action, engage our incident response process, attempt to triage the situation and respond with urgency.

- Remediation: We work to determine the problem and work towards bringing the system or service back to working order.

- Analysis: After the incident, we attempt to learn from the experience, perhaps determining things we might want to change in the system or our process.

- Readiness: We make changes based on what we learned that can improve our reliability and the context (processes and so on) around it.

This module's topic takes place largely during the analysis phase. We learn from incidents by conducting a post-incident review.

You should do a post-incident review after every significant incident.

Although the formal review takes place after the response and remediation phases, you begin to set the stage for your analysis as soon as you receive an actionable alert that an incident has occurred, inform team members, and begin a conversation around the incident.

Defining the post-incident review

Not everyone uses exactly the same language to refer to this process. Some people call it:

- Post-incident review

- Post-incident learning review

- Postmortem

- Retrospective

In this module, we'll use the term "post-incident review."

In addition, not everyone goes about it in exactly the same way. For example, many people start by getting everyone who had any connection to the incident into a room, while other people choose to create the review via individual interviews and then report back to the group.

The latter method often works better when group settings in your organization make a single larger meeting difficult. For example, if group dynamics, personalities, the distributed nature of a team spread over timezones interfere with having that sort of gathering, it might be easier to work on the review in a different way. You should do what works best for your team and the circumstances.

Whatever you call it and however you organize it, there are three key points:

- You should try to include everyone who was involved in the incident response in the post-incident review. Including all of these voices is important because different people will have different perspectives and recollections of the same event.

- You should perform the post-incident review within twenty-four to thirty-six hours after the event, if at all possible. Neuroscience has confirmed that human memory is notoriously unreliable; people forget things. The more time that passes after an event, the less detailed and specific memories tend to be.

- An incident review must be blameless. We talk more about this in the next unit.

Purpose of the post-incident review

The goal of the post-incident review is so your team can learn and improve. You want to learn about the systems and about the things that you had put in place that worked or didn’t work, so you can make improvements.

At the same time, you should remember that action items that you generate—reports, tasks, bug reports, tickets, feedback—are useful, but are peripheral to the point of the process, which is to learn and improve. The generation of a list of action items is at best a secondary goal.