Step 2: Create a Flask app with views and page templates

Applies to: ![]() Visual Studio

Visual Studio ![]() Visual Studio for Mac

Visual Studio for Mac

Note

This article applies to Visual Studio 2017. If you're looking for the latest Visual Studio documentation, see Visual Studio documentation. We recommend upgrading to the latest version of Visual Studio. Download it here

Previous step: Create a Visual Studio project and solution

In step 1 of this tutorial, you created a Flask app with one page and all the code in a single file. To allow future development, it's best to refactor the code and create a structure for page templates. In particular, you want to separate code for the app's views from other aspects like startup code.

In this step you now learn how to:

- Refactor the app's code to separate views from startup code (step 2-1)

- Render a view using a page template (step 2-2)

Step 2-1: Refactor the project to support further development

In the code created by the "Blank Flask Web Project" template, you have a single app.py file that contains startup code alongside a single view. To allow further development of an app with multiple views and templates, it's best to separate these concerns.

In your project folder, create an app folder called

HelloFlask(right-click the project in Solution Explorer and select Add > New Folder.)In the HelloFlask folder, create a file named __init__.py with the following contents that creates the

Flaskinstance and loads the app's views (created in the next step):from flask import Flask app = Flask(__name__) import HelloFlask.viewsIn the HelloFlask folder, create a file named views.py with the following contents. The name views.py is important because you used

import HelloFlask.viewswithin __init__.py; you'll see an error at runtime if the names don't match.from flask import Flask from HelloFlask import app @app.route('/') @app.route('/home') def home(): return "Hello Flask!"In addition to renaming the function and route to

home, this code contains the page rendering code from app.py and imports theappobject that's declared in __init__.py.Create a subfolder in HelloFlask named templates, which remains empty for now.

In the project's root folder, rename app.py to runserver.py, and make the contents match the following code:

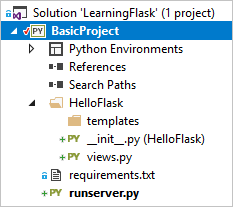

import os from HelloFlask import app # Imports the code from HelloFlask/__init__.py if __name__ == '__main__': HOST = os.environ.get('SERVER_HOST', 'localhost') try: PORT = int(os.environ.get('SERVER_PORT', '5555')) except ValueError: PORT = 5555 app.run(HOST, PORT)Your project structure should look like the following image:

Select Debug > Start Debugging (F5) or use the Web Server button on the toolbar (the browser you see might vary) to start the app and open a browser. Try both the / and /home URL routes.

You can also set breakpoints at various parts of the code and restart the app to follow the startup sequence. For example, set a breakpoint on the first lines of runserver.py and HelloFlask_init_.py, and on the

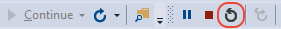

return "Hello Flask!"line in views.py. Then, restart the app (Debug > Restart, Ctrl+Shift+F5, or the toolbar button shown below) and step through (F10) the code, or run from each breakpoint using F5.

When you're done, stop the app.

Commit to source control

After making the changes to the code and testing successfully, you can review and commit your changes to source control. In later steps, when this tutorial reminds you to commit to source control again, you can refer to this section.

Select the changes button along the bottom of Visual Studio (circled below), to navigate to Team Explorer.

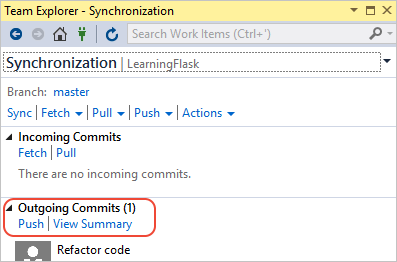

In Team Explorer, enter a commit message like "Refactor code" and select Commit All. When the commit is complete, you see a message Commit <hash> created locally. Sync to share your changes with the server. If you want to push changes to your remote repository, select Sync, then select Push under Outgoing Commits. You can also accumulate multiple local commits before pushing to remote.

Question: How frequently should one commit to source control?

Answer: Committing changes to source control creates a record in the change log and a point to which you can revert the repository if necessary. Each commit can also be examined for its specific changes. Because commits in Git are inexpensive, it's better to do frequent commits than to accumulate a larger number of changes into a single commit. You don't need to commit every small change to individual files. Typically, you make a commit when adding a feature, changing a structure like you've done in this step, or refactoring some code. Also check with others in your team for the granularity of commits that work best for everyone.

How often you commit and how often you push commits to a remote repository are two different concerns. You might accumulate multiple commits in your local repository before pushing them to the remote repository. The frequency of your commits depends on how your team wants to manage the repository.

Step 2-2: Use a template to render a page

The home function that you have so far in views.py generates nothing more than a plain-text HTTP response for the page. However, most real-world web pages, respond with rich HTML pages that often incorporate live data. The primary reason to define a view using a function is to generate content dynamically.

Because the return value for the view is just a string, you can build up any HTML you like within a string, using dynamic content. However, because it's best to separate markup from data, it's better to place the markup in a template and keep the data in code.

For starters, edit views.py to contain the following code that uses inline HTML for the page with some dynamic content:

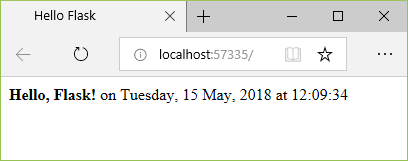

from datetime import datetime from flask import render_template from HelloFlask import app @app.route('/') @app.route('/home') def home(): now = datetime.now() formatted_now = now.strftime("%A, %d %B, %Y at %X") html_content = "<html><head><title>Hello Flask</title></head><body>" html_content += "<strong>Hello Flask!</strong> on " + formatted_now html_content += "</body></html>" return html_contentRun the app and refresh the page a few times to see that the date/time is updated. When you're done, stop the app.

To convert the page rendering to use a template, create a file named index.html in the templates folder with the following content, where

{{ content }}is a placeholder or replacement token (also called a template variable) for which you supply a value in the code:<html> <head><title>Hello Flask</title></head> <body> {{ content }} </body> </html>Modify the

homefunction to userender_templateto load the template and supply a value for "content", which is done using a named argument matching the name of the placeholder. Flask automatically looks for templates in the templates folder, so the path to the template is relative to that folder:def home(): now = datetime.now() formatted_now = now.strftime("%A, %d %B, %Y at %X") return render_template( "index.html", content = "<strong>Hello, Flask!</strong> on " + formatted_now)Run the app and see the results. Observe that the inline HTML in the

contentvalue doesn't render as HTML because the templating engine (Jinja) automatically escapes HTML content. Automatic escaping prevents accidental vulnerabilities to injection attacks. Developers often gather input from one page and use it as a value in another through a template placeholder. Escaping also serves as a reminder that it's best to keep HTML out of the code.Accordingly, review templates\index.html to contain distinct placeholders for each piece of data within the markup:

<html> <head> <title>{{ title }}</title> </head> <body> <strong>{{ message }}</strong>{{ content }} </body> </html>Then update the

homefunction to provide values for all the placeholders:def home(): now = datetime.now() formatted_now = now.strftime("%A, %d %B, %Y at %X") return render_template( "index.html", title = "Hello Flask", message = "Hello, Flask!", content = " on " + formatted_now)Run the app again and see the properly rendered output.

You can commit your changes to source control and update your remote repository. For more information, see step 2-1.

Question: Do page templates have to be in a separate file?

Answer: Although templates are usually maintained in separate HTML files, you can also use an inline template. Separate files are recommended to maintain a clean separation between markup and code.

Question: Must templates use the .html file extension?

Answer: The .html extension for page template files is entirely optional, because you can always identify the exact relative path to the file in the first argument to the render_template function. However, Visual Studio (and other editors) typically give you features like code completion and syntax coloration with .html files, which outweighs the fact that page templates aren't HTML.

When you're working with a Flask project, Visual Studio automatically detects when the HTML file you're editing is actually a Flask template, and provides certain auto-complete features. For example, when you start typing a Flask page template comment, {#, Visual Studio automatically gives you the closing #} characters. The Comment Selection and Uncomment Selection commands (on the Edit > Advanced menu and on the toolbar) also use template comments instead of HTML comments.

Question: Can templates be organized into further subfolders?

Answer: Yes, you can use subfolders and then refer to the relative path under templates in calls to render_template. Doing so is a great way to effectively create namespaces for your templates.

Next steps

Go deeper

- Flask Quickstart - Rendering Templates (flask.pocoo.org)

- Tutorial source code on GitHub: Microsoft/python-sample-vs-learning-flask