CQRS stands for Command and Query Responsibility Segregation, a pattern that separates read and update operations for a data store. Implementing CQRS in your application can maximize its performance, scalability, and security. The flexibility created by migrating to CQRS allows a system to better evolve over time and prevents update commands from causing merge conflicts at the domain level.

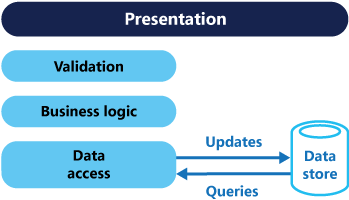

In traditional architectures, the same data model is used to query and update a database. That's simple and works well for basic CRUD operations. In more complex applications, however, this approach can become unwieldy. For example, on the read side, the application may perform many different queries, returning data transfer objects (DTOs) with different shapes. Object mapping can become complicated. On the write side, the model may implement complex validation and business logic. As a result, you can end up with an overly complex model that does too much.

Read and write workloads are often asymmetrical, with very different performance and scale requirements.

There is often a mismatch between the read and write representations of the data, such as additional columns or properties that must be updated correctly even though they aren't required as part of an operation.

Data contention can occur when operations are performed in parallel on the same set of data.

The traditional approach can have a negative effect on performance due to load on the data store and data access layer, and the complexity of queries required to retrieve information.

Managing security and permissions can become complex, because each entity is subject to both read and write operations, which might expose data in the wrong context.

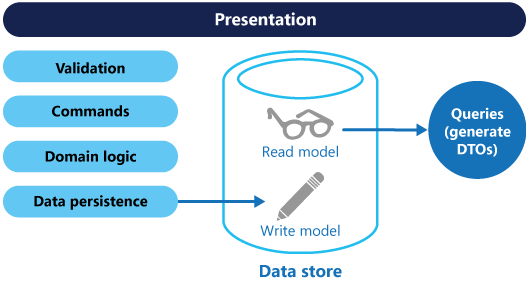

CQRS separates reads and writes into different models, using commands to update data, and queries to read data.

- Commands should be task-based, rather than data centric. ("Book hotel room", not "set ReservationStatus to Reserved"). This may require some corresponding changes to the user interaction style. The other part of that is to look at modifying the business logic processing those commands to be successful more frequently. One technique that supports this is to run some validation rules on the client even before sending the command, possibly disabling buttons, explaining why on the UI ("no rooms left"). In that manner, the cause for server-side command failures can be narrowed to race conditions (two users trying to book the last room), and even those can sometimes be addressed with some more data and logic (putting a guest on a waiting list).

- Commands may be placed on a queue for asynchronous processing, rather than being processed synchronously.

- Queries never modify the database. A query returns a DTO that does not encapsulate any domain knowledge.

The models can then be isolated, as shown in the following diagram, although that's not an absolute requirement.

Having separate query and update models simplifies the design and implementation. However, one disadvantage is that CQRS code can't automatically be generated from a database schema using scaffolding mechanisms such as O/RM tools (However, you will be able to build your customization on top of the generated code).

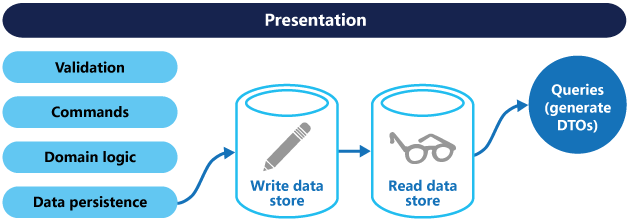

For greater isolation, you can physically separate the read data from the write data. In that case, the read database can use its own data schema that is optimized for queries. For example, it can store a materialized view of the data, in order to avoid complex joins or complex O/RM mappings. It might even use a different type of data store. For example, the write database might be relational, while the read database is a document database.

If separate read and write databases are used, they must be kept in sync. Typically this is accomplished by having the write model publish an event whenever it updates the database. For more information about using events, see Event-driven architecture style. Since message brokers and databases usually cannot be enlisted into a single distributed transaction, there can be challenges in guaranteeing consistency when updating the database and publishing events. For more information, see the guidance on idempotent message processing.

The read store can be a read-only replica of the write store, or the read and write stores can have a different structure altogether. Using multiple read-only replicas can increase query performance, especially in distributed scenarios where read-only replicas are located close to the application instances.

Separation of the read and write stores also allows each to be scaled appropriately to match the load. For example, read stores typically encounter a much higher load than write stores.

Some implementations of CQRS use the Event Sourcing pattern. With this pattern, application state is stored as a sequence of events. Each event represents a set of changes to the data. The current state is constructed by replaying the events. In a CQRS context, one benefit of Event Sourcing is that the same events can be used to notify other components — in particular, to notify the read model. The read model uses the events to create a snapshot of the current state, which is more efficient for queries. However, Event Sourcing adds complexity to the design.

Benefits of CQRS include:

- Independent scaling. CQRS allows the read and write workloads to scale independently, and may result in fewer lock contentions.

- Optimized data schemas. The read side can use a schema that is optimized for queries, while the write side uses a schema that is optimized for updates.

- Security. It's easier to ensure that only the right domain entities are performing writes on the data.

- Separation of concerns. Segregating the read and write sides can result in models that are more maintainable and flexible. Most of the complex business logic goes into the write model. The read model can be relatively simple.

- Simpler queries. By storing a materialized view in the read database, the application can avoid complex joins when querying.

Some challenges of implementing this pattern include:

Complexity. The basic idea of CQRS is simple. But it can lead to a more complex application design, especially if they include the Event Sourcing pattern.

Messaging. Although CQRS does not require messaging, it's common to use messaging to process commands and publish update events. In that case, the application must handle message failures or duplicate messages. See the guidance on Priority Queues for dealing with commands having different priorities.

Eventual consistency. If you separate the read and write databases, the read data may be stale. The read model store must be updated to reflect changes to the write model store, and it can be difficult to detect when a user has issued a request based on stale read data.

Consider CQRS for the following scenarios:

Collaborative domains where many users access the same data in parallel. CQRS allows you to define commands with enough granularity to minimize merge conflicts at the domain level, and conflicts that do arise can be merged by the command.

Task-based user interfaces where users are guided through a complex process as a series of steps or with complex domain models. The write model has a full command-processing stack with business logic, input validation, and business validation. The write model may treat a set of associated objects as a single unit for data changes (an aggregate, in DDD terminology) and ensure that these objects are always in a consistent state. The read model has no business logic or validation stack, and just returns a DTO for use in a view model. The read model is eventually consistent with the write model.

Scenarios where performance of data reads must be fine-tuned separately from performance of data writes, especially when the number of reads is much greater than the number of writes. In this scenario, you can scale out the read model, but run the write model on just a few instances. A small number of write model instances also helps to minimize the occurrence of merge conflicts.

Scenarios where one team of developers can focus on the complex domain model that is part of the write model, and another team can focus on the read model and the user interfaces.

Scenarios where the system is expected to evolve over time and might contain multiple versions of the model, or where business rules change regularly.

Integration with other systems, especially in combination with event sourcing, where the temporal failure of one subsystem shouldn't affect the availability of the others.

This pattern isn't recommended when:

The domain or the business rules are simple.

A simple CRUD-style user interface and data access operations are sufficient.

Consider applying CQRS to limited sections of your system where it will be most valuable.

An architect should evaluate how the CQRS pattern can be used in their workload's design to address the goals and principles covered in the Azure Well-Architected Framework pillars. For example:

| Pillar | How this pattern supports pillar goals |

|---|---|

| Performance Efficiency helps your workload efficiently meet demands through optimizations in scaling, data, code. | The separation of read and write operations in high read-to-write workloads enables targeted performance and scaling optimizations for each operation's specific purpose. - PE:05 Scaling and partitioning - PE:08 Data performance |

As with any design decision, consider any tradeoffs against the goals of the other pillars that might be introduced with this pattern.

The CQRS pattern is often used along with the Event Sourcing pattern. CQRS-based systems use separate read and write data models, each tailored to relevant tasks and often located in physically separate stores. When used with the Event Sourcing pattern, the store of events is the write model, and is the official source of information. The read model of a CQRS-based system provides materialized views of the data, typically as highly denormalized views. These views are tailored to the interfaces and display requirements of the application, which helps to maximize both display and query performance.

Using the stream of events as the write store, rather than the actual data at a point in time, avoids update conflicts on a single aggregate and maximizes performance and scalability. The events can be used to asynchronously generate materialized views of the data that are used to populate the read store.

Because the event store is the official source of information, it is possible to delete the materialized views and replay all past events to create a new representation of the current state when the system evolves, or when the read model must change. The materialized views are in effect a durable read-only cache of the data.

When using CQRS combined with the Event Sourcing pattern, consider the following:

As with any system where the write and read stores are separate, systems based on this pattern are only eventually consistent. There will be some delay between the event being generated and the data store being updated.

The pattern adds complexity because code must be created to initiate and handle events, and assemble or update the appropriate views or objects required by queries or a read model. The complexity of the CQRS pattern when used with the Event Sourcing pattern can make a successful implementation more difficult, and requires a different approach to designing systems. However, event sourcing can make it easier to model the domain, and makes it easier to rebuild views or create new ones because the intent of the changes in the data is preserved.

Generating materialized views for use in the read model or projections of the data by replaying and handling the events for specific entities or collections of entities can require significant processing time and resource usage. This is especially true if it requires summation or analysis of values over long periods, because all the associated events might need to be examined. Resolve this by implementing snapshots of the data at scheduled intervals, such as a total count of the number of a specific action that has occurred, or the current state of an entity.

The following code shows some extracts from an example of a CQRS implementation that uses different definitions for the read and the write models. The model interfaces don't dictate any features of the underlying data stores, and they can evolve and be fine-tuned independently because these interfaces are separated.

The following code shows the read model definition.

// Query interface

namespace ReadModel

{

public interface ProductsDao

{

ProductDisplay FindById(int productId);

ICollection<ProductDisplay> FindByName(string name);

ICollection<ProductInventory> FindOutOfStockProducts();

ICollection<ProductDisplay> FindRelatedProducts(int productId);

}

public class ProductDisplay

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public string Description { get; set; }

public decimal UnitPrice { get; set; }

public bool IsOutOfStock { get; set; }

public double UserRating { get; set; }

}

public class ProductInventory

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public int CurrentStock { get; set; }

}

}

The system allows users to rate products. The application code does this using the RateProduct command shown in the following code.

public interface ICommand

{

Guid Id { get; }

}

public class RateProduct : ICommand

{

public RateProduct()

{

this.Id = Guid.NewGuid();

}

public Guid Id { get; set; }

public int ProductId { get; set; }

public int Rating { get; set; }

public int UserId {get; set; }

}

The system uses the ProductsCommandHandler class to handle commands sent by the application. Clients typically send commands to the domain through a messaging system such as a queue. The command handler accepts these commands and invokes methods of the domain interface. The granularity of each command is designed to reduce the chance of conflicting requests. The following code shows an outline of the ProductsCommandHandler class.

public class ProductsCommandHandler :

ICommandHandler<AddNewProduct>,

ICommandHandler<RateProduct>,

ICommandHandler<AddToInventory>,

ICommandHandler<ConfirmItemShipped>,

ICommandHandler<UpdateStockFromInventoryRecount>

{

private readonly IRepository<Product> repository;

public ProductsCommandHandler (IRepository<Product> repository)

{

this.repository = repository;

}

void Handle (AddNewProduct command)

{

...

}

void Handle (RateProduct command)

{

var product = repository.Find(command.ProductId);

if (product != null)

{

product.RateProduct(command.UserId, command.Rating);

repository.Save(product);

}

}

void Handle (AddToInventory command)

{

...

}

void Handle (ConfirmItemsShipped command)

{

...

}

void Handle (UpdateStockFromInventoryRecount command)

{

...

}

}

The following patterns and guidance are useful when implementing this pattern:

Data Consistency Primer. Explains the issues that are typically encountered due to eventual consistency between the read and write data stores when using the CQRS pattern, and how these issues can be resolved.

Horizontal, vertical, and functional data partitioning. Describes best practices for dividing data into partitions that can be managed and accessed separately to improve scalability, reduce contention, and optimize performance.

The patterns & practices guide CQRS Journey. In particular, Introducing the Command Query Responsibility Segregation pattern explores the pattern and when it's useful, and Epilogue: Lessons Learned helps you understand some of the issues that come up when using this pattern.

Martin Fowler's blog posts:

Event Sourcing pattern. Describes in more detail how Event Sourcing can be used with the CQRS pattern to simplify tasks in complex domains while improving performance, scalability, and responsiveness. As well as how to provide consistency for transactional data while maintaining full audit trails and history that can enable compensating actions.

Materialized View pattern. The read model of a CQRS implementation can contain materialized views of the write model data, or the read model can be used to generate materialized views.

Presentation on better CQRS through asynchronous user interaction patterns