Decompose a task that performs complex processing into a series of separate elements that can be reused. Doing so can improve performance, scalability, and reusability of initial steps by allowing task elements that perform the processing to be deployed and scaled independently. Pipes and Filters pattern supports a high level of modularity.

You have a pipeline of sequential tasks that you need to process. A straightforward but inflexible approach to implement this application is to perform this processing in a monolithic module. However, this approach is likely to reduce the opportunities for refactoring the code, optimizing it, or reusing it if parts of the same processing are required elsewhere in the application.

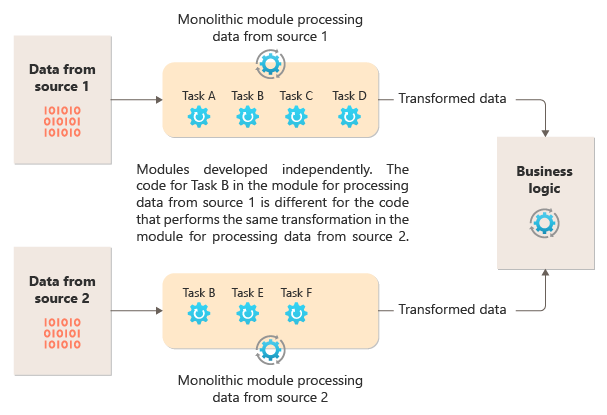

The following diagram illustrates one of the problems with processing data using a monolithic approach, the inability to reuse code across multiple pipelines. In this example, an application receives and processes data from two sources. A separate module processes the data from each source by performing a series of tasks to transform the data before passing the result to the business logic of the application.

Some of the tasks that the monolithic modules perform are functionally similar, but the code has to be repeated in both modules and is likely tightly coupled within its module. In addition to the inability to reuse logic, this approach introduces a risk when requirements change. You must remember to update the code in both places.

There are other challenges with a monolithic implementation unrelated to multiple pipelines or reuse. With a monolith, you don't have the ability to run specific tasks in different environments or scale them independently. Some tasks might be compute-intensive and would benefit from running on powerful hardware or running multiple instances in parallel. Other tasks might not have the same requirements. Further, with monoliths, it's challenging to reorder tasks or to inject new tasks in the pipeline. These changes require retesting the entire pipeline.

Break down the processing required for each stream into a set of separate components (or filters), each performing a single task. Composite tasks should use multiple filters rather than one. The filters are composed into pipelines by connecting the filters with pipes. Filters are independent, self-contained, and typically stateless. Filters receive messages from an inbound pipe and publish messages to a different outbound pipe. Filters can transform the message or test it against one or more criteria to include conditional logic. Pipes don't perform routing or any other logic. They only connect filters, passing the output message from one filter as the input to the next.

Filters act independently and are unaware of other filters. They're only aware of their input and output schemas. As such, the filters can be arranged in any order so long as the input schema for any filter matches the output schema for the previous filter. Using a standardized schema for all filters enhances the ability to reorder filters. Pipes and filters architecture encourages compositional reuse.

The loose coupling of filters makes it easy to:

- Create new pipelines composed of existing filters

- Update or replace logic in individual filters

- Reorder filters, when necessary

- Run filters on differing hardware, where required

- Run filters in parallel

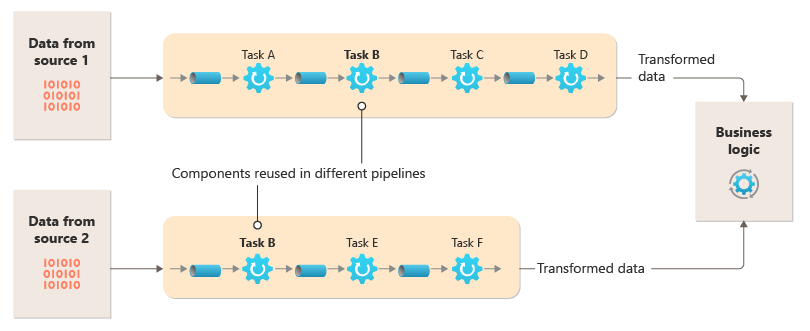

This diagram shows a solution implemented with pipes and filters:

The time it takes to process a single request depends on the speed of the slowest filters in the pipeline. One or more filters could be bottlenecks, especially if a high number of requests appear in a stream from a particular data source. The ability to run parallel instances of slow filters enables the system to spread the load and improve throughput.

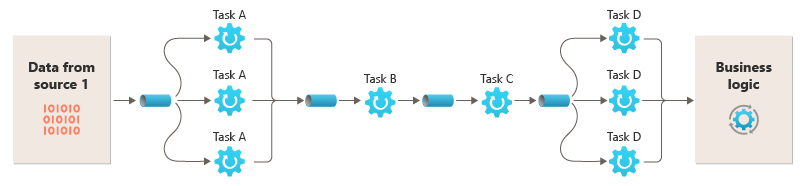

The ability to run filters on different compute instances enables them to be scaled independently and take advantage of the elasticity that many cloud environments provide. A filter that's computationally intensive can run on high-performance hardware, while other less-demanding filters can be hosted on less-expensive commodity hardware. The filters don't even need to be in the same datacenter or geographic location, enabling each element in a pipeline to run in an environment that's close to the resources it requires. These efforts require specific design techniques such as messaging, multi-threading, and so on to maximize the elasticity of each pipe or filter. This diagram shows an example applied to the pipeline for the data from Source 1:

If the input and output of a filter are structured as a stream, you can perform the processing for each filter in parallel. The first filter in the pipeline can start its work and output its results, which are passed directly to the next filter in the sequence before the first filter completes its work.

Using the Pipes and Filters pattern together with the Compensating Transaction pattern is an alternative approach to implementing distributed transactions. You can break a distributed transaction into separate, compensable tasks, each of which can be implemented via a filter that also implements the Compensating Transaction pattern. You can implement the filters in a pipeline as separate hosted tasks that run close to the data that they maintain.

Consider the following points when you decide how to implement this pattern:

Monolithic nature. This pattern is usually implemented as a monolithic pipeline, so for any change, the entire filter chain should be tested end to end. Also, fault-tolerance for the whole process needs to be considered; if a filter or pipe fails, the whole pipeline is likely to fail.

Complexity. The increased flexibility that this pattern provides can also introduce complexity, especially if the filters in a pipeline are distributed across different servers.

Reliability. Use an infrastructure that ensures that data flowing between filters in a pipe aren't lost.

Idempotency. If a filter in a pipeline fails after receiving a message and the work is rescheduled to another instance of the filter, part of the work might already be complete. If the work updates some aspect of the global state (like information stored in a database), a single update could be repeated. A similar issue might occur if a filter fails after it posts its results to the next filter, but before it indicates that it completed its work successfully. In these cases, another instance of the filter could repeat this work, causing the same results to be posted twice. This scenario could result in subsequent filters in the pipeline processing the same data twice. Therefore, filters in a pipeline should be designed to be idempotent. For more information, see Idempotency Patterns on Jonathan Oliver's blog.

Repeated messages. If a filter in a pipeline fails after it posts a message to the next stage of the pipeline, another instance of the filter might be run, and it would post a copy of the same message to the pipeline. This scenario could cause two instances of the same message to be passed to the next filter. To avoid this problem, the pipeline should detect and eliminate duplicate messages.

Note

If you implement the pipeline by using message queues (like Azure Service Bus queues), the message queuing infrastructure might provide automatic duplicate message detection and removal.

Context and state. In a pipeline, each filter essentially runs in isolation and shouldn't make any assumptions about how it was invoked. Therefore, each filter should be provided with sufficient context to perform its work. This context could include a significant amount of state information. If filters use external state, such as data in a database or external storage, then you must consider the impact on performance. Every filter has to load, operate, and persist that state, which adds overhead over solutions that load the external state a single time.

Message tolerance. Filters must be tolerant of data in the incoming message that they don't operate against. They operate on the data pertinent to them and ignore other data and pass it along unchanged in the output message.

Error handling - Every filter must determine what to do in the case of a breaking error. The filter must determine if it fails the pipeline or propagates the exception.

Use this pattern when:

The processing required by an application can easily be broken down into a set of independent steps.

The processing steps performed by an application have different scalability requirements.

Note

You can group filters that should scale together in the same process. For more information, see the Compute Resource Consolidation pattern.

You require the flexibility to allow reordering of the processing steps the application performs, or to allow the capability to add and remove steps.

The system can benefit from distributing the processing for steps across different servers.

You need a reliable solution that minimizes the effects of failure in a step while data is being processed.

This pattern might not be useful when:

The application follows a request-response pattern.

The task processing must be completed as part an initial request, such as a request/response scenario.

The processing steps performed by an application aren't independent, or they have to be performed together as part of a single transaction.

The amount of context or state information a step requires makes this approach inefficient. You might be able to persist state information to a database, but don't use this strategy if the extra load on the database causes excessive contention.

An architect should evaluate how the Pipes and Filters pattern can be used in their workload's design to address the goals and principles covered in the Azure Well-Architected Framework pillars. For example:

| Pillar | How this pattern supports pillar goals |

|---|---|

| Reliability design decisions help your workload become resilient to malfunction and to ensure that it recovers to a fully functioning state after a failure occurs. | The single responsibility of each stage enables focused attention and avoids the distraction of commingled data processing. - RE:01 Simplicity - RE:07 Background jobs |

As with any design decision, consider any tradeoffs against the goals of the other pillars that might be introduced with this pattern.

You can use a sequence of message queues to provide the infrastructure required to implement a pipeline. An initial message queue receives unprocessed messages that become the start of the pipes and filters pattern implementation. A component implemented as a filter task listens for a message on this queue, performs its work, and then posts a new or transformed message to the next queue in the sequence. Another filter task can listen for messages on this queue, process them, post the results to another queue, and so on, until the final step that ends the pipes and filters process. This diagram illustrates a pipeline that uses message queues:

An image processing pipeline could be implemented using this pattern. If your workload takes an image, the image could pass through a series of largely independent and reorderable filters to perform actions such as:

- content moderation

- resizing

- watermarking

- reorientation

- Exif metadata removal

- Content delivery network (CDN) publication

In this example, the filters could be implemented as individually deployed Azure Functions or even a single Azure Function app that contains each filter as an isolated deployment. The use of Azure Function triggers, input bindings, and output bindings can simplify the filter code and work automatically with a queue-based pipe using a claim check to the image to process.

Here's an example of what one filter, implemented as an Azure Function, triggered from a Queue Storage pipe with a claim Check to the image, and writing a new claim check to another Queue Storage pipe might look like. We've replaced the implementation with pseudocode in comments for brevity. More code like this can be found in the demonstration of the Pipes and Filters pattern available on GitHub.

// This is the "Resize" filter. It handles claim checks from input pipe, performs the

// resize work, and places a claim check in the next pipe for anther filter to handle.

[Function(nameof(ResizeFilter))]

[QueueOutput("pipe-fjur", Connection = "pipe")] // Destination pipe claim check

public async Task<string> RunAsync(

[QueueTrigger("pipe-xfty", Connection = "pipe")] string imageFilePath, // Source pipe claim check

[BlobInput("{QueueTrigger}", Connection = "pipe")] BlockBlobClient imageBlob) // Image to process

{

_logger.LogInformation("Processing image {uri} for resizing.", imageBlob.Uri);

// Idempotency checks

// ...

// Download image based on claim check in queue message body

// ...

// Resize the image

// ...

// Write resized image back to storage

// ...

// Create claim check for image and place in the next pipe

// ...

_logger.LogInformation("Image resizing done or not needed. Adding image {filePath} into the next pipe.", imageFilePath);

return imageFilePath;

}

Note

The Spring Integration Framework has an implementation of the pipes and filters pattern.

You might find the following resources helpful when you implement this pattern:

- A demonstration of the Pipes and Filters Pattern using the image processing scenario is available on GitHub.

- Idempotency patterns, on Jonathan Oliver's blog.

The following patterns might also be relevant when you implement this pattern:

- Claim-Check pattern. A pipeline implemented using a queue may not hold the actual item being sent through the filters, but instead a pointer to the data that needs to be processed. The example uses a claim check in Azure Queue Storage for images stored in Azure Blob Storage.

- Competing Consumers pattern. A pipeline can contain multiple instances of one or more filters. This approach is useful for running parallel instances of slow filters. It enables the system to spread the load and improve throughput. Each instance of a filter competes for input with the other instances, but two instances of a filter shouldn't be able to process the same data. This article explains the approach.

- Compute Resource Consolidation pattern. It might be possible to group filters that should scale together into a single process. This article provides more information about the benefits and tradeoffs of this strategy.

- Compensating Transaction pattern. You can implement a filter as an operation that can be reversed, or that has a compensating operation that restores the state to a previous version if there's a failure. This article explains how you can implement this pattern to maintain or achieve eventual consistency.

- Pipes and Filters - Enterprise Integration Patterns.