Coordinate a set of distributed actions as a single operation. If any of the actions fail, try to handle the failures transparently, or else undo the work that was performed, so the entire operation succeeds or fails as a whole. This can add resiliency to a distributed system, by enabling it to recover and retry actions that fail due to transient exceptions, long-lasting faults, and process failures.

An application performs tasks that include a number of steps, some of which might invoke remote services or access remote resources. The individual steps might be independent of each other, but they are orchestrated by the application logic that implements the task.

Whenever possible, the application should ensure that the task runs to completion and resolve any failures that might occur when accessing remote services or resources. Failures can occur for many reasons. For example, the network might be down, communications could be interrupted, a remote service might be unresponsive or in an unstable state, or a remote resource might be temporarily inaccessible, perhaps due to resource constraints. In many cases the failures will be transient and can be handled by using the Retry pattern.

If the application detects a more permanent fault it can't easily recover from, it must be able to restore the system to a consistent state and ensure integrity of the entire operation.

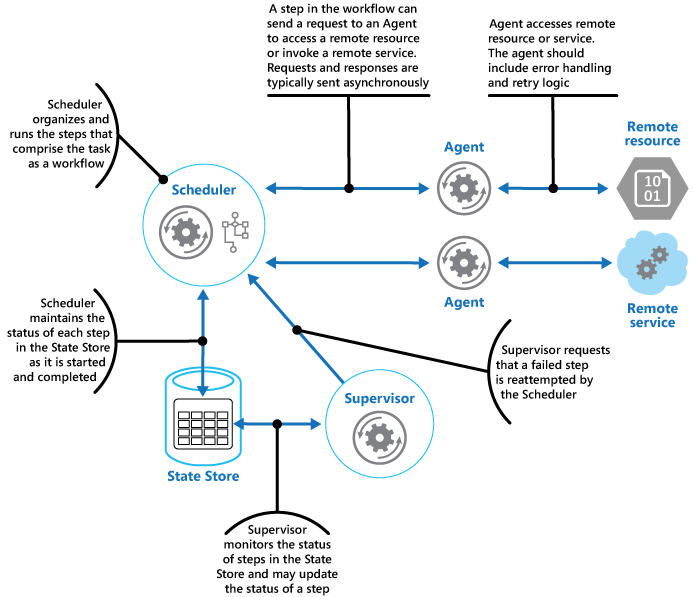

The Scheduler Agent Supervisor pattern defines the following actors. These actors orchestrate the steps to be performed as part of the overall task.

The Scheduler arranges for the steps that make up the task to be executed and orchestrates their operation. These steps can be combined into a pipeline or workflow. The Scheduler is responsible for ensuring that the steps in this workflow are performed in the right order. As each step is performed, the Scheduler records the state of the workflow, such as "step not yet started," "step running," or "step completed." The state information should also include an upper limit of the time allowed for the step to finish, called the complete-by time. If a step requires access to a remote service or resource, the Scheduler invokes the appropriate Agent, passing it the details of the work to be performed. The Scheduler typically communicates with an Agent using asynchronous request/response messaging. This can be implemented using queues, although other distributed messaging technologies could be used instead.

The Scheduler performs a similar function to the Process Manager in the Process Manager pattern. The actual workflow is typically defined and implemented by a workflow engine that's controlled by the Scheduler. This approach decouples the business logic in the workflow from the Scheduler.

The Agent contains logic that encapsulates a call to a remote service, or access to a remote resource referenced by a step in a task. Each Agent typically wraps calls to a single service or resource, implementing the appropriate error handling and retry logic (subject to a timeout constraint, described later). When implementing retry logic, pass a stable identifier across all retry attempts so that the remote service can use it for any deduplication logic it may have. If the steps in the workflow being run by the Scheduler use several services and resources across different steps, each step might reference a different Agent (this is an implementation detail of the pattern).

The Supervisor monitors the status of the steps in the task being performed by the Scheduler. It runs periodically (the frequency will be system-specific), and examines the status of steps maintained by the Scheduler. If it detects any that have timed out or failed, it arranges for the appropriate Agent to recover the step or execute the appropriate remedial action (this might involve modifying the status of a step). Note that the recovery or remedial actions are implemented by the Scheduler and Agents. The Supervisor should simply request that these actions be performed.

The Scheduler, Agent, and Supervisor are logical components and their physical implementation depends on the technology being used. For example, several logical agents might be implemented as part of a single web service.

The Scheduler maintains information about the progress of the task and the state of each step in a durable data store, called the state store. The Supervisor can use this information to help determine whether a step has failed. The figure illustrates the relationship between the Scheduler, the Agents, the Supervisor, and the state store.

Note

This diagram shows a simplified version of the pattern. In a real implementation, there might be many instances of the Scheduler running concurrently, each a subset of tasks. Similarly, the system could run multiple instances of each Agent, or even multiple Supervisors. In this case, Supervisors must coordinate their work with each other carefully to ensure that they don't compete to recover the same failed steps and tasks. The Leader Election pattern provides one possible solution to this problem.

When the application is ready to run a task, it submits a request to the Scheduler. The Scheduler records initial state information about the task and its steps (for example, step not yet started) in the state store and then starts performing the operations defined by the workflow. As the Scheduler starts each step, it updates the information about the state of that step in the state store (for example, step running).

If a step references a remote service or resource, the Scheduler sends a message to the appropriate Agent. The message contains the information that the Agent needs to pass to the service or access the resource, in addition to the complete-by time for the operation. If the Agent completes its operation successfully, it returns a response to the Scheduler. The Scheduler can then update the state information in the state store (for example, step completed) and perform the next step. This process continues until the entire task is complete.

An Agent can implement any retry logic that's necessary to perform its work. However, if the Agent doesn't complete its work before the complete-by period expires, the Scheduler will assume that the operation has failed. In this case, the Agent should stop its work and not try to return anything to the Scheduler (not even an error message), or try any form of recovery. The reason for this restriction is that, after a step has timed out or failed, another instance of the Agent might be scheduled to run the failing step (this process is described later).

If the Agent fails, the Scheduler won't receive a response. The pattern doesn't make a distinction between a step that has timed out and one that has genuinely failed.

If a step times out or fails, the state store will contain a record that indicates that the step is running, but the complete-by time will have passed. The Supervisor looks for steps like this and tries to recover them. One possible strategy is for the Supervisor to update the complete-by value to extend the time available to complete the step, and then send a message to the Scheduler identifying the step that has timed out. The Scheduler can then try to repeat this step. However, this design requires the tasks to be idempotent. The system should contain infrastructure to maintain consistency. For more information, see Repeatable Infrastructure, Architect Azure applications for resiliency and availability, and Resource consistency decision guide.

The Supervisor might need to prevent the same step from being retried if it continually fails or times out. To do this, the Supervisor could maintain a retry count for each step, along with the state information, in the state store. If this count exceeds a predefined threshold the Supervisor can adopt a strategy of waiting for an extended period before notifying the Scheduler that it should retry the step, in the expectation that the fault will be resolved during this period. Alternatively, the Supervisor can send a message to the Scheduler to request the entire task be undone by implementing a Compensating Transaction pattern. This approach will depend on the Scheduler and Agents providing the information necessary to implement the compensating operations for each step that completed successfully.

It isn't the purpose of the Supervisor to monitor the Scheduler and Agents, and restart them if they fail. This aspect of the system should be handled by the infrastructure these components are running in. Similarly, the Supervisor shouldn't have knowledge of the actual business operations that the tasks being performed by the Scheduler are running (including how to compensate should these tasks fail). This is the purpose of the workflow logic implemented by the Scheduler. The sole responsibility of the Supervisor is to determine whether a step has failed and arrange either for it to be repeated or for the entire task containing the failed step to be undone.

If the Scheduler is restarted after a failure, or the workflow being performed by the Scheduler terminates unexpectedly, the Scheduler should be able to determine the status of any inflight task that it was handling when it failed, and be prepared to resume this task from that point. The implementation details of this process are likely to be system-specific. If the task can't be recovered, it might be necessary to undo the work already performed by the task. This might also require implementing a compensating transaction.

The key advantage of this pattern is that the system is resilient in the event of unexpected temporary or unrecoverable failures. The system can be constructed to be self-healing. For example, if an Agent or the Scheduler fails, a new one can be started and the Supervisor can arrange for a task to be resumed. If the Supervisor fails, another instance can be started and can take over from where the failure occurred. If the Supervisor is scheduled to run periodically, a new instance can be automatically started after a predefined interval. The state store can be replicated to reach an even greater degree of resiliency.

You should consider the following points when deciding how to implement this pattern:

This pattern can be difficult to implement and requires thorough testing of each possible failure mode of the system.

The recovery/retry logic implemented by the Scheduler is complex and dependent on state information held in the state store. It might also be necessary to record the information required to implement a compensating transaction in a durable data store. A compensating transaction might fail as well.

How often the Supervisor runs will be important. It should run often enough to prevent any failed steps from blocking an application for an extended period, but it shouldn't run so often that it becomes an overhead.

The steps performed by an Agent could be run more than once. The logic that implements these steps should be idempotent.

Use this pattern when a process that runs in a distributed environment, such as the cloud, must be resilient to communications failure and/or operational failure.

This pattern might not be suitable for tasks that don't invoke remote services or access remote resources.

An architect should evaluate how the Scheduler Agent Supervisor pattern can be used in their workload's design to address the goals and principles covered in the Azure Well-Architected Framework pillars. For example:

| Pillar | How this pattern supports pillar goals |

|---|---|

| Reliability design decisions help your workload become resilient to malfunction and to ensure that it recovers to a fully functioning state after a failure occurs. | This pattern uses health metrics to detect failures and reroute tasks to a healthy agent in order to mitigate the effects of a malfunction. - RE:05 Redundancy - RE:07 Self-healing |

| Performance Efficiency helps your workload efficiently meet demands through optimizations in scaling, data, code. | This pattern uses performance and capacity metrics to detect current utilization and route tasks to an agent that has capacity. You can also use it to prioritize the execution of higher priority work over lower priority work. - PE:05 Scaling and partitioning - PE:09 Critical flows |

As with any design decision, consider any tradeoffs against the goals of the other pillars that might be introduced with this pattern.

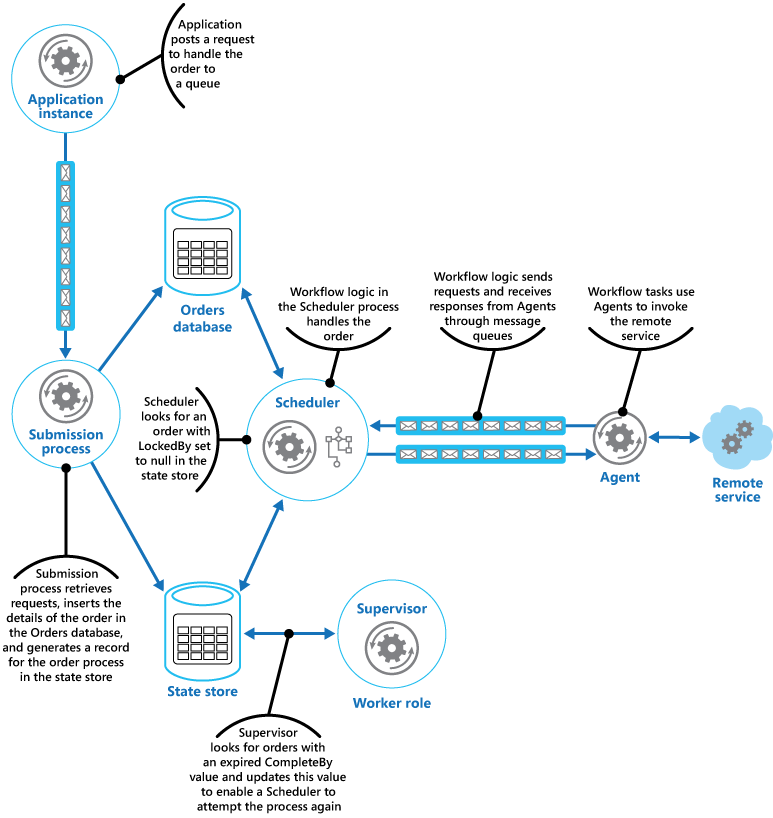

A web application that implements an ecommerce system has been deployed on Microsoft Azure. Users can run this application to browse the available products and to place orders. The user interface runs as a web role, and the order processing elements of the application are implemented as a set of worker roles. Part of the order processing logic involves accessing a remote service, and this aspect of the system could be prone to transient or more long-lasting faults. For this reason, the designers used the Scheduler Agent Supervisor pattern to implement the order processing elements of the system.

When a customer places an order, the application constructs a message that describes the order and posts this message to a queue. A separate submission process, running in a worker role, retrieves the message, inserts the order details into the orders database, and creates a record for the order process in the state store. Note that the inserts into the orders database and the state store are performed as part of the same operation. The submission process is designed to ensure that both inserts complete together.

The state information that the submission process creates for the order includes:

OrderID. The ID of the order in the orders database.

LockedBy. The instance ID of the worker role handling the order. There might be multiple current instances of the worker role running the Scheduler, but each order should only be handled by a single instance.

CompleteBy. The time the order should be processed by.

ProcessState. The current state of the task handling the order. The possible states are:

- Pending. The order has been created but processing hasn't yet been started.

- Processing. The order is currently being processed.

- Processed. The order has been processed successfully.

- Error. The order processing has failed.

FailureCount. The number of times that processing has been tried for the order.

In this state information, the OrderID field is copied from the order ID of the new order. The LockedBy and CompleteBy fields are set to null, the ProcessState field is set to Pending, and the FailureCount field is set to 0.

Note

In this example, the order handling logic is relatively simple and only has a single step that invokes a remote service. In a more complex multistep scenario, the submission process would likely involve several steps, and so several records would be created in the state store — each one describing the state of an individual step.

The Scheduler also runs as part of a worker role and implements the business logic that handles the order. An instance of the Scheduler polling for new orders examines the state store for records where the LockedBy field is null and the ProcessState field is pending. When the Scheduler finds a new order, it immediately populates the LockedBy field with its own instance ID, sets the CompleteBy field to an appropriate time, and sets the ProcessState field to processing. The code is designed to be exclusive and atomic to ensure that two concurrent instances of the Scheduler can't try to handle the same order simultaneously.

The Scheduler then runs the business workflow to process the order asynchronously, passing it the value in the OrderID field from the state store. The workflow handling the order retrieves the details of the order from the orders database and performs its work. When a step in the order processing workflow needs to invoke the remote service, it uses an Agent. The workflow step communicates with the Agent using a pair of Azure Service Bus message queues acting as a request/response channel. The figure shows a high-level view of the solution.

The message sent to the Agent from a workflow step describes the order and includes the complete-by time. If the Agent receives a response from the remote service before the complete-by time expires, it posts a reply message on the Service Bus queue on which the workflow is listening. When the workflow step receives the valid reply message, it completes its processing and the Scheduler sets the ProcessState field of the order state to processed. At this point, the order processing has completed successfully.

If the complete-by time expires before the Agent receives a response from the remote service, the Agent simply halts its processing and terminates handling the order. Similarly, if the workflow handling the order exceeds the complete-by time, it also terminates. In both cases, the state of the order in the state store remains set to processing, but the complete-by time indicates that the time for processing the order has passed and the process is deemed to have failed. Note that if the Agent that's accessing the remote service, or the workflow that's handling the order (or both) terminate unexpectedly, the information in the state store will again remain set to processing and eventually will have an expired complete-by value.

If the Agent detects an unrecoverable, nontransient fault while it's trying to contact the remote service, it can send an error response back to the workflow. The Scheduler can set the status of the order to error and raise an event that alerts an operator. The operator can then try to resolve the reason for the failure manually and resubmit the failed processing step.

The Supervisor periodically examines the state store looking for orders with an expired complete-by value. If the Supervisor finds a record, it increments the FailureCount field. If the failure count value is below a specified threshold value, the Supervisor resets the LockedBy field to null, updates the CompleteBy field with a new expiration time, and sets the ProcessState field to pending. An instance of the Scheduler can pick up this order and perform its processing as before. If the failure count value exceeds a specified threshold, the reason for the failure is assumed to be nontransient. The Supervisor sets the status of the order to error and raises an event that alerts an operator.

In this example, the Supervisor is implemented in a separate worker role. You can use a variety of strategies to arrange for the Supervisor task to be run, including using the Azure Scheduler service (not to be confused with the Scheduler component in this pattern). For more information about the Azure Scheduler service, visit the Scheduler page.

Although it isn't shown in this example, the Scheduler might need to keep the application that submitted the order informed about the progress and status of the order. The application and the Scheduler are isolated from each other to eliminate any dependencies between them. The application has no knowledge of which instance of the Scheduler is handling the order, and the Scheduler is unaware of which specific application instance posted the order.

To allow the order status to be reported, the application could use its own private response queue. The details of this response queue would be included as part of the request sent to the submission process, which would include this information in the state store. The Scheduler would then post messages to this queue indicating the status of the order (request received, order completed, order failed, and so on). It should include the order ID in these messages so they can be correlated with the original request by the application.

The following guidance might also be relevant when implementing this pattern:

Asynchronous Messaging Primer. The components in the Scheduler Agent Supervisor pattern typically run decoupled from each other and communicate asynchronously. Describes some of the approaches that can be used to implement asynchronous communication based on message queues.

Reference 6: A Saga on Sagas. An example showing how the CQRS pattern uses a process manager (part of the CQRS Journey guidance).

The following patterns might also be relevant when implementing this pattern:

Retry pattern. An Agent can use this pattern to transparently retry an operation that accesses a remote service or resource that has previously failed. Use when the expectation is that the cause of the failure is transient and can be corrected.

Circuit Breaker pattern. An Agent can use this pattern to handle faults that take a variable amount of time to correct when connecting to a remote service or resource.

Compensating Transaction pattern. If the workflow being performed by a Scheduler can't be completed successfully, it might be necessary to undo any work it's previously performed. The Compensating Transaction pattern describes how this can be achieved for operations that follow the eventual consistency model. These types of operations are commonly implemented by a Scheduler that performs complex business processes and workflows.

Leader Election pattern. It might be necessary to coordinate the actions of multiple instances of a Supervisor to prevent them from attempting to recover the same failed process. The Leader Election pattern describes how to do this.

Cloud Architecture: The Scheduler-Agent-Supervisor pattern on Clemens Vasters' blog